Second time lucky? Timeline of unreported changes to the research protocol, NHMRC homeopathy review

A key undertaking provided by the Department of Health for the new 2019-20 review updates of 16 natural therapies is to pre-publish the research protocols to be used. This is an important transparency measure routinely observed in ethical scientific processes to safeguard them against research malpractice and bias.

This decision has a historical basis. In the previous 2012-15 reviews of 16 natural therapies undertaken by the National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the research protocols were not pre-published and the reports released in 2015 did not provide full disclosure. Why?

This article provides a detailed timeline, for the public record, of post-hoc changes made to the research protocol for the first natural therapy reviewed in 2012-15 (homeopathy), and how these changes impacted the findings. The approach developed for this review provided the template for how the other 15 natural therapies were assessed. For further background to the genesis of these reviews, read here.

These details are included in a Complaint being investigated by the Commonwealth Ombudsman of alleged misconduct in the 2015 NHMRC Homeopathy Review.

The problem of research malpractice:

Misconduct/fraud in clinical research is recognised as a widespread problem and is surprisingly common in the conduct of health-related systematic reviews [1]. The NHMRC recognises this issue and states that it “takes all research integrity matters very seriously“. According to the NHMRC Fraud Control Framework 2020-22:

“NHMRC refuses to tolerate fraud and has a commitment to high ethical, moral and legal standards.”

Two of the commonest features of research malpractice are the failure to follow the agreed research protocol (including making midstream changes in the absence of full disclosure and justification) and inadequate/inaccurate reporting of methods and results [2].

The importance of research protocols:

Before a study begins, a protocol (the investigation plan) is created which outlines in detail all essential aspects of the project, such as the research question being asked, methods of data retrieval, criteria used to determine which studies will be included or excluded from the review, and how the included data will be analysed to produce the final results.

Making significant ‘post-hoc’ (midstream) changes is a recognised source of bias as the reviewers may, consciously or subconsciously, alter the method to achieve a pre-desired result. Any changes made to the protocol must be fully disclosed and justified.

This is why protocols are often published before a study begins so that once the final study is published, other researchers can see whether the original protocol was followed correctly and independently assess any post-hoc changes that were made. It is an important safeguard protecting against fraudulent conduct that undermines the scientific process and public trust.

PROSPERO:

To counter such problems, in February 2011 the open-access database International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) was launched for research groups to prospectively register reviews on health-related topics.

“PROSPERO aims to provide a comprehensive listing of systematic reviews registered at inception to help avoid duplication and reduce opportunity for reporting bias by enabling comparison of the completed review with what was planned in the original protocol.”

In the 2019-20 Natural Therapy Review, the Department of Health has informed stakeholders that the NHMRC will prospectively register the research protocol for each natural therapy with PROSPERO, for transparency and to safeguard against bias.

PROSPERO only accepts reviews provided that data extraction has not yet started, “to reduce potential for bias by reducing the opportunity for (conscious or subconscious) selection or manipulation of data during extraction to shape a review so that it reaches a desired conclusion.”

NHMRC and the PROSPERO advisory group:

PROSPERO is supported and guided by an international advisory group that includes the NHMRC’s Prof Davina Ghersi, who was also involved in the establishment of PROSPERO in late 2010/2011 [3]. This was over a year before the NHMRC homeopathy review formally commenced on 4 April 2012.

The Freedom of Information (FOI) record shows that Prof Ghersi was also involved in the NHMRC homeopathy review during 2012 and 2013, alongside the Chair of NHMRC Homeopathy Working Committee (HWC), Bond University’s Prof Paul Glasziou. She liaised with the contractors, was a key contributor at HWC meetings, and was directly involved in developing the methodology.

The missing first review:

Documents released under FOI in 2016 revealed that the NHMRC engaged in two attempts at reviewing the evidence on homeopathy. The report released on 11 March 2015, which concluded there was ‘no reliable evidence’, was in fact the second attempt.

The existence of a first review conducted between April and August 2012 by the University of South Australia (UniSA), which reported positive findings for homeopathy in some conditions, was not disclosed to taxpayers. Since the existence of the review was not made public, the pre-agreed research protocol was also not known.

FOI documents show that on 12 July 2012, HWC member Prof Fred Mendelsohn provided the following advice to NHMRC on a draft version of the UniSA report [4],

“I am impressed by the rigour, thoroughness and systematic approach given to this evaluation … Overall, a lot of excellent work has gone into this review and the results are presented in a systematic, unbiased and convincing manner.”

The contractor submitted their final draft report on 1 August 2012 and “after discussions with the contractor on 3 August” the NHMRC terminated their contract [5]. After initially considering completing the work themselves [5], the NHMRC instead decided to engage a new contractor, OptumInsight (Optum), and start again. The 2015 NHMRC Administrative Report (p.6) states that Optum was commissioned in October 2012 to review the evidence – without disclosing any of the preceding events.

Following is a general overview of what happened during the second attempt. This is followed by an in-depth, fully referenced timeline for those who wish to acquaint themselves with the ‘behind the scenes’ details of what occurred during the Optum review. This information is published in the public domain for transparency and accountability, as it was not disclosed or reported by the NHMRC in over 944 pages of published documentation.

Overview of undisclosed changes to the Optum review research protocol:

The (first) UniSA and (second) Optum reviews reached different conclusions on the basis of essentially the same data set. How did the Optum review conclude there was ‘no reliable evidence’, whereas the UniSA review concluded there was ‘encouraging evidence’ in several conditions?

The FOI record shows that the research protocol for the Optum review was finalised and approved between all parties (NHMRC, HWC and Optum) in late December 2012 [6] and that Optum completed its assessment between January and March 2013 according to it specifications [7].

The protocol was not prospectively published on a registry such as PROSPERO (or equivalent) or ever made publicly available.

Since the approved protocol was not published, how closely Optum followed it was not able to be determined, however, the minutes of the first HWC meeting held in March 2018 to discuss the findings show that the approved protocol was not fully followed [7].

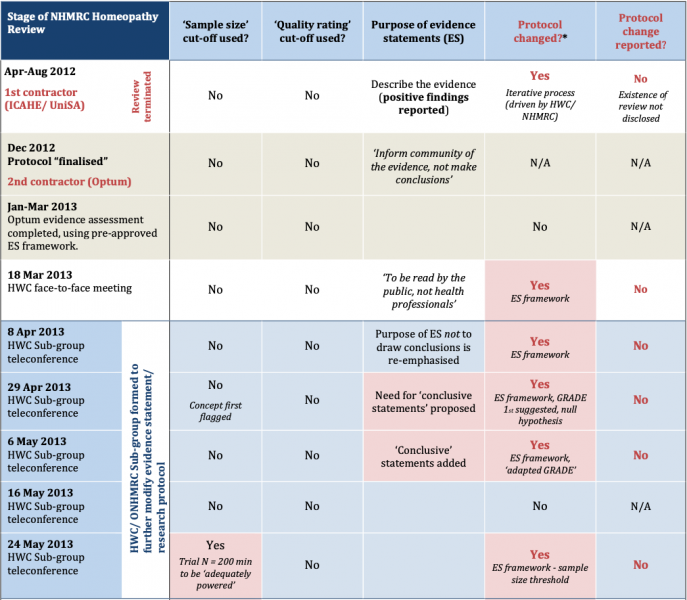

FOI documents reveal that the Office of NHMRC/ HWC then convened a Sub-group from April 2013 to ‘further refine’ the protocol [8]. FOI records show that over the coming months, a new framework was created around a unique concept of ‘reliable evidence’, which continued to be modified and refined until August 2013. The final version, which bore no resemblance in any respect to the protocol originally approved in December 2012, was an entirely novel framework that had never been used before (or since) by the NHMRC or any other research group or agency in the world.

None of the post-hoc changes made to the original protocol, or their impact on the findings, were disclosed/reported.

Impact of post-hoc protocol changes on review’s findings:

Independent assessment of NHMRC’s method and procedures post-publication of the 2015 report has shown that the changes made directly resulted in 171 out of the 176 studies included in the Optum overview being retrospectively categorised as ‘not reliable’. This meant that the results of these studies were ‘not considered any further’ and therefore did not contribute to the review’s findings.

Even though these 171 studies were technically included in the review and described in the Optum Overview Report, their results were dismissed from the review’s findings as ‘unreliable’. This important analysis was not included in the Optum Overview Report or in any NHMRC documentation.

Since the 5 remaining ‘reliable’ trials were judged to be negative, the NHMRC reported an overall finding of ‘no reliable evidence’ in any of the 61 conditions examined.

The timeline of retrospective, undisclosed changes made to the research protocol during the 2012-15 NHMRC homeopathy review (as revealed by the FOI record) is summarised in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: Timeline of changes to NHMRC (Optum) Homeopathy Review research protocol & process used for drafting evidence statements (‘ES framework’) *For details of protocol changes see main text.

Second time lucky? A detailed timeline of post-hoc changes to the research protocol

The NHMRC has defended allegations that it manipulated the research protocol during the second (Optum) review in any way that altered the findings, or that it misleadingly reported its methods and findings. This has been referred to the Commonwealth Ombudsman for independent review. The NHMRC states that the review was conducted ‘ethically’ and ‘transparently’, citing its reputation for excellence, integrity and position of public trust.

Read the following timeline of events and judge for yourself.

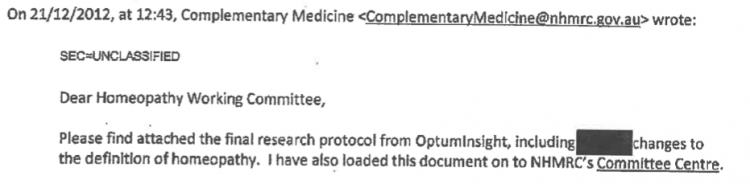

December 2012 – Optum review research protocol finalised and approved:

Documents released under FOI in 2016 show that the original research protocol for the Optum Review was finalised and approved by the NHMRC, Optum and the HWC in late December 2012, prior to Optum commencing the work [6].

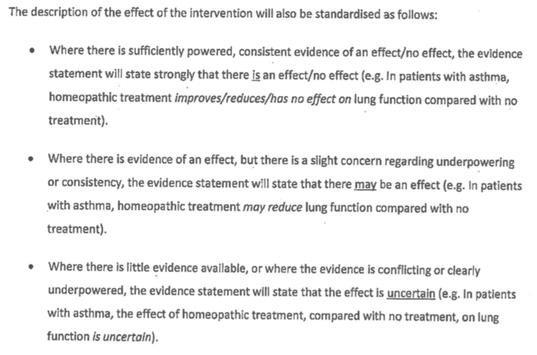

The final approved protocol, which was never published, revealed that the following ‘standardised’ framework was to be applied by Optum when developing evidence statements against each health condition assessed [6]:

Of particular note is that this evidence statement framework protocol bears no resemblance, in any respect, to the one published in the NHMRC Information Paper (Appendix C) and Optum Overview Report (Appendix C).

It is also noteworthy that the protocol approved in December 2012 allows for uncertainty in the findings, which is common in systematic reviews, especially in areas (such as homeopathy) where a large body of evidence is not available.

So how did the protocol change, when did this occur and were these changes and their impact on the findings reported?

Detailed timeline of post-hoc changes to the research protocol:

January-March 2013 – Optum completes evidence assessment:

After the original research protocol was finalised and approved in December 2012, Optum conducted its data extraction and evidence assessment between 3 January and March 2013. The HWC then convened on 18 March 2013 to discuss the findings and consider the draft evidence statements [7].

The minutes of the March 2013 HWC meeting show that when developing draft evidence statements, the original protocol was not followed because it would have found that the evidence for homeopathy was “uncertain” (i.e. not negative) [7]. From this point, the FOI record shows that a decision was made to deviate from the originally approved protocol in order to alter the results of the review to reach more definitive conclusions, as described below.

Apr-May 2013 – HWC Sub-group established to ‘refine’ the research protocol:

To do this, the NHMRC established a HWC Sub-group, which convened between 8 April and 24 May 2013 for the purpose of ‘refining’ the evidence statement framework [8]. The existence of the Sub-group process or its actions was not disclosed in the Optum Overview Report, NHMRC Information Paper or Administrative Report, or elsewhere.

It is important to note that at this point in time, Optum had already conducted its evidence evaluation according to the specifications of the pre-agreed research protocol (as described above).

At the first Sub-group meeting on 8 April, none of the criteria used in the final evidence statement framework yet existed [9]. All elements of the final framework were developed and retrospectively applied to the assessment over the coming months, as part of an iterative process where unreported changes were made to the protocol along the way (Fig. 1).

8 April 2013 – inaugural Sub-group meeting:

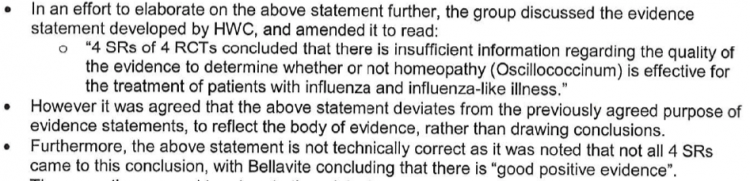

The minutes of the inaugural Sub-group meeting on 8 April record the intention to redraft the pre-agreed evidence statement protocol. The group reaffirmed the purpose of the evidence statements, “to reflect the body of evidence, rather than drawing conclusions about the effectiveness of homeopathy”. This was later changed to make them ‘conclusive’ (see below, Fig. 1).

The minutes of the 8 April meeting show how the group grappled with developing evidence statements for conditions where positive, good quality positive evidence existed for homeopathy (such as childhood diarrhoea and influenza), as well as how the process itself was deviating from the pre-approved protocol [9]:

29 April 2013 – ‘null hypothesis approach’ first proposed:

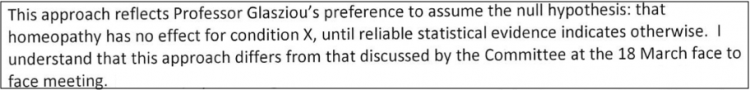

The 2015 NHMRC Information Paper (Appendix C, p.38) states that the ‘null hypothesis approach’ was applied to the evaluation, meaning it was ‘assumed’ that “homeopathy has no effect as a treatment for that condition unless there was sufficient reliable evidence to demonstrate otherwise”.

What the Information Paper does not disclose is that this was not part of the original protocol. It was first introduced by the HWC Chair (Prof Paul Glasziou) midstream in late April 2013 [10, 11], weeks after Optum had completed its assessment. The revision was formally adopted at the 29 April HWC Sub-group meeting.

An email from the NHMRC to the HWC on 30 April obtained under FOI evidences this change, alongside an acknowledgement by the NHMRC secretariat that it represented a midstream change in approach [10]:

It is also important to note use of the term ‘reliable’ evidence – what does this mean?

By this stage of the review (late April/ early May 2013), the HWC/ NHMRC/ Optum themselves had no idea what it meant, as the criteria/ elements that comprised the ‘reliable evidence’ framework had not yet been developed. In fact, even the concept of ‘reliable evidence’ did not formally exist at this time.

The FOI record shows that this framework was developed over the following months, gradually sculpted into its final form as part of an ‘iterative process’.

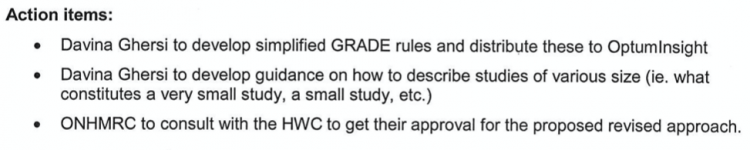

29 Apr 2013 – ‘adapted GRADE’ tool & ‘conclusive statements’ introduced:

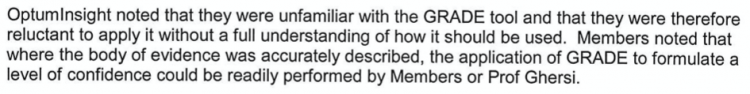

FOI documents reveal that at the 29 April Sub-group meeting, Prof Davina Ghersi (NHMRC) first proposed the use of the ‘GRADE’ tool to provide a ‘level of confidence (LOC)’ rating of the evidence [11]. This was to eventually become ‘Element 2‘ of the final evidence statement framework.

Optum stated that it was “unfamiliar with the GRADE tool” and was “reluctant to apply it without a full understanding of how it should be used”. Therefore, Prof Ghersi undertook to develop a novel ‘adapted’ version of it specifically for the review, and that she and/or the HWC would apply it on Optum’s behalf [11]:

The ‘need’ for introducing “conclusive statements” as a new element of the evidence statement framework was also first introduced. This was a fundamental shift from the original protocol agreed in December 2012, which specified that the purpose of the review was to “inform the community of the evidence” and “not draw conclusions” (acknowledging and allowing for the uncertainty that invariably exists in research evidence). ‘Conclusive statements’ was introduced as a new element (Element 3) of the revised, still incomplete protocol.

At the 29 April meeting, the idea of categorising studies by their ‘size’ was also first flagged as a concept. An action item was for Prof Ghersi (NHMRC) to consider and develop this idea further between meetings for the HWC’s later consideration. The development of this criterion ended up having a profound impact on the review’s outcome (as shown below in the timeline).

The FOI record shows that it was also noted that the NHMRC would need to:

“consult with the HWC to get their approval for the proposed revised approach”

This shows the key role the NHMRC played in driving the process. The FOI record also shows the primary role that the HWC Chair, Prof Paul Glasziou, also played.

The minutes of the 29 April meeting stated, “any agreed approach would then be applied going forwards” – acknowledging that the protocol was being modified post-hoc with a view to applying it retrospectively to Optum’s evidence assessment, which had already been completed according to the specifications of the originally agreed (unpublished) protocol [11].

6 May 2013 – HWC approves revised draft evidence statement framework

The new ‘revised’ framework was approved by the HWC at its teleconference meeting on 6 May 2013, including the new ‘adapted GRADE’ tool [12].

The meeting minutes record discussion on how the framework could be applied to a number of conditions for which good quality, positive evidence existed for homeopathy (such as diarrhoea in children, otitis media, ADHD, fibromyalgia, influenza-like illness), which the first (UniSA) reviewer had framed as ‘encouraging’ evidence.

The FOI record shows that the NHMRC/HWC grappled with developing consistent statements for these conditions. To resolve the deadlock, the NHMRC undertook to draft example evidence statements for the “top 16 priority conditions” for the HWC to consider at later meetings [12].

This resulted in a series of further refinements to the protocol’s continually evolving evidence statement framework:

24 May 2013 – ‘sample size’ threshold concept first introduced:

The 2015 NHMRC Information Paper (Appendix C, p.35) states that one of the criteria for a trial to be ‘reliable’ is that it had to have a minimum of 150 trial participants.

What NHMRC documentation doesn’t explain/disclose is that the concept of using trial sample size as an exclusion threshold did not exist in the originally agreed protocol, or that the concept of using trial size as an exclusion threshold was not flagged until May 2013 – two months after Optum had completed its evidence assessment [13].

NHMRC public documentation also does not reveal that when this concept was first conceived it was not linked to trial ‘reliability’: this was only revealed in documents released under FOI.

The FOI record shows that at the 24 May 2013 HWC Sub-group meeting, Prof Ghersi (NHMRC) first proposed a sample size threshold of 200 participants for whether a trial was ‘adequately powered’. This was introduced as a new component of Element 1 of the constantly evolving evidence statement framework [13].

9 July 2013 – First round methodological peer review, ACC:

The NHMRC Information Paper (p.15) states,

“NHMRC commissioned an independent organisation with expertise in research methodology (The Australasian Cochrane Centre) to review the methods used in the overview and ensure that processes for identifying and assessing the evidence were scientifically rigorous, consistently applied, and clearly documented.”

NHMRC did not publish the ACC’s advice, which was obtained through FOI [14]. On 9 July 2013, the ACC peer-reviewed the draft report and advised the NHMRC/HWC:

– linking sample size to whether a trial is ‘adequately powered’ was not scientifically valid

– there were fundamental flaws with the novel ‘adapted GRADE’ tool. This is because GRADE is designed to be used when describing primary research evidence, whereas the NHMRC review only accessed secondary sources (systematic reviews) that omitted and/or incompletely reported essential primary source information (as it is not their purpose to provide detailed primary trial data).

– the draft evidence statements were overly-definitive and did not allow for uncertainty in the research (which the original protocol approved in December 2012 allowed for, in line with usual practice).

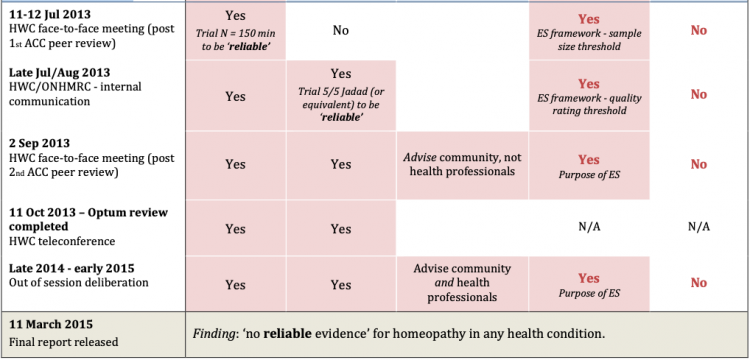

11-12 July 2013 – HWC face-to-face meeting, revised sample size exclusion threshold approved:

As a result of the ACC’s advice, the NHMRC/ HWC dropped the minimum N=200 sample size threshold for whether a trial was ‘adequately powered’. Instead, it replaced it with a new minimum threshold of N=150 sample size for whether a trial was ‘reliable’.

At its 11-12 July 2013 face-to-face meeting, the HWC agreed to the new N=150 sample size threshold for trial ‘reliability’, which was added to Element 1 of the evidence statement framework [15]. This is when the concept of ‘reliable evidence’ first appears.

It is noteworthy that NHMRC routinely conducts studies with less than 150 participants, which are never classified as ‘unreliable’.

The impact of this decision was momentous in the context of the review, but this is not possible to ascertain as the core data was not provided anywhere in over 900 pages of review documentation published by the NHMRC (highly unusual for a ‘rigorous’ scientific review). The impact of the N=150 sample size rule had to be pieced together through independent scientific forensic investigation, which involved retrieval of each of the original 176 published trials included in the review.

Impact of the N=150 rule – independent evaluation:

Independent evaluation has shown that in its own right, the N=150 rule to determine whether a trial was ‘reliable’ dismissed the results of 146 out of the 176 included trials from ‘being considered any further’ as part of the review’s findings [16].

In other words, since 146 of the 176 trials had fewer than 150 trials participants their findings were not considered as part of the review’s findings – irrespective of whether trials reported positive findings that were statistically significant. These trials were still described in the Optum Overview report, but the N=150 sample size ‘rule’ prevented them from contributing to the review’s overall findings published in the NHMRC Information Paper (as they were ‘unreliable’).

The fact that the N=150 criterion was introduced as part of Element 1 of the evidence statement framework several months after Optum had completed its evidence assessment (and seven months after the original protocol was approved) was also not reported.

Late July/ August 2013 – ‘quality rating scale’ threshold added:

After 146 of the 176 trials were excluded from contributing to the review’s findings (as they did not meet the N=150 sample size threshold), 30 trials remained that were ‘reliable’ by virtue of having greater than 150 trial participants. These included trials concluding positive clinical outcomes for homeopathic treatments.

The FOI record reveals that the NHMRC/HWC subsequently introduced an additional ‘quality rating’ threshold at some stage in late July/ August 2013, which was added as an additional requirement to Element 1 of the evidence statement protocol for a trial to be ‘reliable’ [17].

Thus, a trial now also had to be rated an unusually high 5/5 on the Jadad (or equivalent) quality rating scale for it to be considered ‘good quality’ and hence ‘reliable’.

This change to the protocol and its impact on the findings was not reported.

Independent evaluation has shown that the ‘quality rating’ criterion directly dismissed the results of 25 out of the remaining 30 trials from ‘being considered any further’ as part of the Review’s findings [16].

This left only 5 ‘reliable’ trials – i.e. trials having both greater than 150 trial participants AND a quality rating of 5/5 Jadad (or equivalent).

Remaining ‘reliable’ trial:

All 5 remaining ‘reliable’ trials were deemed to be negative, which facilitated an overall conclusion that there was ‘no reliable evidence that homeopathy worked in any health condition’ – the overall finding published in the NHMRC Information Paper and Statement on Homeopathy.

However, one of the 5 remaining ‘reliable’ trials was in fact positive: a ‘good’ quality trial (rated 5/5 Jadad) on lower back pain with 161 trial participants. In Table 1 of the NHMRC Information Paper, this trial was substituted with a negative trial in the same condition that was not one of the 176 trials included in the main overview.

This was the only identifiable error in Table 1 of the NHMRC Information Paper.

A quarter of the 176 trials “assumed” to be substandard quality, without original papers being checked:

The NHMRC also did not report that for 44 of the 176 trials (25% of the data), the ‘quality’ of these trials could not be determined, as the secondary-source information (systematic reviews) relied upon didn’t report it.

Instead of retrieving the original studies to check, the NHMRC/HWC instead invented a ‘rule’ to assume they were ‘not good quality’. A consequence of this was that they were also deemed to be ‘not reliable’. This occurred without any scientific evaluation to fill in this essential data gap pertaining to a core criterion specified in the revised protocol (as detailed in Appendix C of the NHMRC Information Paper, pp.35-36).

FAQ: ‘All 176 trials seem to be included in the NHMRC overview, not just 5 trials’

The NHMRC media release of 11 March 2015 misleadingly announced that the results of its review were based on a “rigorous assessment of over 1800 studies” [18], despite the fact that only 176 studies were accepted for inclusion in the Optum overview (Optum’s initial data extraction identified over 1800 papers, most of which were excluded from scope of the overview and included several hundred duplicate citations).

The NHMRC Information Paper correctly states that these 176 studies were described and evaluated in the Optum Overview Report. In this respect, they were ‘included’ in the overview.

However, if a trial did not meet the minimum ‘N=150 participants’ AND/OR ‘5/5 Jadad (or equivalent) quality rating’ thresholds, they were deemed to be ‘unreliable’. This meant their results (whether positive, negative or inconclusive) were dismissed as they did not ‘warrant further consideration of their findings’. As the NHMRC Information Paper itself confirms (Appendix C, p.36):

“If there was more than one study that suggested that homeopathy is more effective than placebo or as effective as other therapies but due to the number, size and/or quality of those studies the findings are not reliable, a general statement to that effect was made, for example: ‘These studies are of insufficient [quality] / [size] / [quality and size] / [quality and/or size] / [quality or size] to warrant further consideration of their findings.”

Neither the Information Paper nor any other NHMRC review documentation disclosed/reported that this framework in fact dismissed the results of 171 out of the 176 studies from contributing to the findings.

30 August 2013 – Second round methodological peer review, ACC:

In late August 2013, the ACC provided second-round peer-review feedback on the revised draft report and made a number of key observations and recommendations that were not reported or followed up, advising:

“There are instances where our initial concerns about a particular methodological approach stand”

This feedback in particular related to the ‘adapted GRADE’ tool, as well as the accuracy of the overall findings. The ACC also noted that post-hoc changes to the research protocol had been made, which had not been fully disclosed or adequately explained.

For example, the ACC noted,

‘The document now specifies cutoffs for applying qualitative descriptors of quality for different tools (p2). …’ (which did not exist in the draft report peer-reviewed in July 2013) and advised, “Empirical evidence has shown that using quality scales to identify trials of high quality is problematic”.

The ACC also critiqued the overly-definitive nature of the review’s findings, which it noted was not consistent with the existence of a significant proportion of small, but good quality studies. It advised NHMRC/HWC (emphasis added):

“If the intent is to provide general statements about the effectiveness of homeopathy, then ‘no reliable evidence’ may not adequately reflect the research. For example, when a substantial proportion of small (but good quality) studies show significant differences, […] ‘no reliable evidence’ does not seem an accurate reflection of the body of evidence.”

This is consistent with the findings of the terminated original review by the University of South Australia conducted in 2012, which concluded that there was ‘encouraging evidence’ for homeopathy in a number of health conditions.

The FOI record shows that the HWC dealt with the ACC feedback by changing the purpose of the evidence statements, from ‘informing‘ the community of the evidence (the purpose of the review, as framed in the original protocol) to, “advise members of the community about the effectiveness of homeopathy to support informed healthcare decisions/ choices“.

In the eyes of the NHMRC/HWC, this subtle and confusing shift in nuance seemed to satisfactorily resolve the ACC’s critique regarding the accuracy of the review’s conclusion (although it is unclear how this scientifically addressed the ACC critique).

Neither the 9 July nor the 30 August 2013 ACC feedback was publicly disclosed, despite the NHMRC releasing a dedicated ‘Expert Review Comments’ document alongside the Information Paper [19]. It had to be obtained through FOI [14, 17].

Additional undisclosed peer-review comments, 2014:

The NHMRC ‘Expert Review Comments’ document also heavily redacted adverse feedback provided by another expert peer-reviewer in May 2014, after the draft report was released for public comment on 9 April 2014. The expert reviewer’s feedback was also obtained through FOI, revealing concerns expressed to NHMRC that overlapped with that provided by the ACC. The reviewer’s feedback was also disregarded and withheld from the public eye.

Following is the text of the expert reviewer’s feedback to NHMRC – the text highlighted in red represents text that the NHMRC selectively omitted from inclusion in its published ‘Expert Review Comments’ document [20]:

“The dismissal of positive systematic reviews compounded with the lack of an independent systematic review of high quality randomised controlled trials leaves me uncertain of the definitive nature of the Report’s conclusions. […]

High quality RCTs with narrow confidence intervals (Level 1 evidence) should have been searched for and included in this review.

Systematic reviews (SRs) have considerable weaknesses as reliable sources of evidence. Personally, I would prefer a much more reserved approach to their use as Level 1 evidence. For example, we know that SRs can come to quite contrasting conclusions pending the grading RCT scale they adopt. (See Juni et al, JAMA, 1999). High quality clinical trial designs in homeopathy should accommodate for tailoring of treatment but this is generally not weighted in the rating scales used by reviewers. If tailoring of treatment is critical in homeopathy then it may be that only low quality studies, as defined by the common grading metrics, will exhibit positive outcomes. [This is because tailoring of treatment may have resulted in un-blinding of the intervention group.] Some systematic reviews conclude homeopathy is more than placebo (Cucherat et al 2000; Linde & Melchart 1998; Linde et al 1997; Kleijnen 1991; and many of the reviews in the Swiss report found a trend in favour of homeopathy). It is probably unreasonable to discount this evidence on the basis that good quality trials did not show such strong evidence of efficacy, if the quality rating scale for trials is not well justified for use in homeopathy. Hence, the usual conclusion that high quality trials demonstrate less favourable outcomes than poor quality trials does not really hold.

Quality rating scales have seldom been tested for inter-rater reliability, there is a lack of agreement between scales as to what is being measured, and scales differ in many respects including items for inclusion and number of items. The NHMRC Report should address this issue more explicitly. […]

… if I were to dispassionately consider the evidence of efficacy, I am still left with niggling doubts that there are unanswered questions around the evidence. […] Finally, I am concerned that no homeopathic expert was appointed to the NHMRC Review Panel. I cannot imagine this being agreed in oncology, orthopaedics or other disciplines.”

NHMRC policy on research integrity:

The NHMRC, as the peak medical research agency in Australia, creates the rules that it expects all medical researchers to follow and states that it, “takes all research integrity matters very seriously“.

All research funded by the NHMRC is required to comply with the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research, 2018, as part of the NHMRC Research Integrity and Misconduct Policy.

Did the NHMRC uphold and model its statutory integrity framework in its conduct of the 2015 Homeopathy Review? Or did it actively steer the review towards a pre-determined conclusion that was ideologically palatable to the conservative scientific community it draws from and represents?

With the fuller facts on the table, you be the judge.

Sources:

[1] , et al (2016). How do authors of systematic reviews deal with research malpractice and misconduct in original studies? A cross-sectional analysis of systematic reviews and survey of their authors.

[2] Gupta A. (2013). Fraud and misconduct in clinical research: A concern. Perspectives in clinical research, 4(2), 144–147. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-3485.111800

[3] Booth, A., Clarke, M., Dooley, G., Ghersi, D., Moher, D., Petticrew, M., Stewart, L. (2012). The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst Rev 1, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-2

[4] 12 Jul 2012. Feedback to NHMRC from HWC member Prof Fred Mendelsohn on the July 2012 version of the first (UniSA) reviewer’s Draft Report. NHMRC FOI 2014/15 021-08 & NHMRC FOI 2016/17 016-Doc 13

[5] 13 Aug 2012 – Email between Office of NHMRC & HWC Chair Paul Glasziou re termination of UniSA contract. NHMRC FOI 2014/15 021-Doc 10

[6] 21 Dec 2012. Email from NHMRC to Optum & HWC members with final research protocol for the Optum Homeopathy Review. NHMRC FOI 2014/15 004-Section 58

[7] 18 March 2013. HWC face-to-face meeting minutes. NHMRC FOI 2015/16 007-Doc 3

[8] Minutes of HWC and HWC Sub Group meetings 2013-2014. NHMRC FOI 2015/16 008

[9] 8 Apr 2013. Minutes of inaugural HWC Sub-group teleconference meeting to discuss evidence statements. NHMRC FOI 2015/16 008-Doc 1

[10] 30 Apr 2013. Email from ONHMRC to HWC members re. ‘null hypothesis’ approach to homeopathy evidence statements. NHMRC FOI 2014/15 021-Doc 11

[11] 29 Apr 2013. HWC Sub Group teleconference meeting minutes. NHMRC FOI 2015/16 008-Doc 2

[12] 6 May 2013. HWC Sub Group teleconference meeting minutes. NHMRC FOI 2015/16 008-Doc 3

[13] 24 May 2013. HWC Sub Group teleconference meeting minutes. 24.05.2013. NHMRC FOI 2015/16 008-Doc 5

[14] 9 Jul 2013. First-round Australasian Cochrane Centre (ACC) methodological peer review. NHMRC FOI 2015-16 008-Doc 13

[15] 11-12 Jul 2013. HWC face-to-face meeting minutes. NHMRC FOI 2015-16 008-Doc 6

[16] Homeopathy Research Institute (HRI). Data extracted from NHMRC’s Table 1 (Information Paper, p.18- 20), with analysis of the combined impact of ‘reliability’ thresholds for trial sample size and quality. https://www.hri-research.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/HRI-data-analysis-impact-of-NHMRC-definition-of-reliable.pdf

[17] 30 Aug 2013. Australasian Cochrane Centre (ACC) second-round methodological peer review. NHMRC FOI 2015-16 007-Doc 5

[18] 11 Mar 2015. NHMRC Releases Statement and Advice on Homeopathy (media release)

[19] 11 Mar 2015. Summary of key issues: Draft information paper on homeopathy—expert review comments. NHMRC cam02e. Available at: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/resources/homeopathy

[20] 10 May 2014. NHMRC Expert Reviewer feedback re. Draft Information paper on homeopathy. NHMRC FOI 2014/15 004-Section 62

SIGN below to support scientific integrity and hold government processes to account.

« Return to News & Features